Author: Linn Karlsson

Pierre Thiam

Teranga Man

There’s far more to West African food than jollof, the famous one-pot-rice dish found all over the region. Rich in ingredients yet soon to become mainstream in Europe or America. Ever heard of fonio? Well it could soon replace rice in your larder. Keen to know more? Then Pierre Thiam is your man. A New York based Senegalese author and chef bringing light to food from the West of the continent.

Published 16/02/2020

DK

PT

DK

PT

Yes, Teranga is one of the highest values in Senegal. Hospitality is something that Sen-egalese people take very seriously. It’s much wider than hospitality, because it’s a way of life. You go to Senegal, you are treated as a guest of honor really, even if you’re not expected. You meet someone and they will give you Teranga at its best. When you come to a house, where lunch or dinner is being served, even if you’re not expected, you’ll be invited and that’s a strong value. Even if food is not being served, you’ll be offered something or a drink, either a hibiscus or a ginger drink. Teranga is a value that Senegalese strongly believe in. They strongly believe that by sharing what they have and giving the best of what they have they’ll receive blessings in return. That’s Teranga.

«Hospitality is something that Senegalese people take very seriously.»

DK

PT

I guess I’ll start with the national dish, it’s called Thiéboudienne. It’s similar to paella in a sense. It is rice cooked in a rich tomato broth, a broth flavored with fish. Sometimes there’s even other seafood like shrimp inside. That’s if you are making Thiéboudienne Sous which is like the deluxe Thiéboudienne. It also has vegetables like root vegetables, cassava, carrots, sometimes eggplants,

cabbage. The particularity of the flavoring, and this you see throughout Senegalese dishes, is the fermentation. That is the most common seasoning. Often they use a fermented guedge but sometimes it’s fermented locust bean called nététou, or even dried fish that’s been steeped under the sun with salt and beef and rice. All that adds a really particular flavor, a particular funk to the dish that makes it really special. You also have dishes from the South. One is called Yassa, which contains onion sauce with lime and is used with grilled chicken or fish over Jasmine rice.

Salmon & cassava croquettes with tamarind glaze

DK

PT

Fonio is an ancient grain that’s been cultivated for over 5,000 years in Africa.

It’s probably the oldest cultivated grain. It’s delicious and very delicate. Nutty flavor, very versatile and nutritious. It’s rich in amino acids, cysteine, and methionine. These are rare in most grains, so that’s particular to fonio. In addition to that, it’s great for the environment. It’s a grain that is drought resistant, grows in poor soil and matures really quickly. It cooks quickly too! Fonio cooks within five minutes. It’s an amazing grain. It’s a grain that has

a lot of benefits in addition to being easy to cook with. In Mali, the Bambara people have a saying: “Fonio never embarrasses the cook,” because that’s how easy it is to prepare.

Prawns in coconut & lime over millet couscous thiéré

DK

PT

Nem is of Vietnamese origin, it’s their spring rolls. There is a community of Vietnamese that arrived in Senegal around colonial times because the French used to have an empire that spread from Senegal, all the way to Southeast Asia including Vietnam. That was Indochina at the time.

There were some troubles, of course. People fought for their liberation and the French colonial army was called Le Tirailleurs Sénégalais, that was like the Senegalese Battalion in a sense.

They would send of course the African soldiers from the colonial empire to fight the Vietnamese. When they had to leave Vietnam, a big community of Vietnamese followed them, those ones who were on the wrong side of the war I guess.

They came to Senegal and have been established for some time now. They came with their food and we love the food. It became a big part of our food. Particularly the Nem. You don’t go to a name birthing ceremony in Senegal without having them.

DK

PT

I have a new book coming out this fall. This one will be actually be focusing on fonio. Following the agriculture of fonio. I travelled with a photographer, documenting the harvesting, processing and traditional preparation of fonio as well as imagining recipes that are suited for a New York kitchen. Collaborating with a great photographer named Adam Bartos. I’m very excited about it. It should come out this fall.

Published 16/02/2020

By DK Woon

Photo credits Sara Costa

Bibi Seck

The Problem Solver

Bibi Seck is the boy who never stopped drawing. His passion has taken him all over the world, corralled into the world of design. Drawing allows him to unfurl his imagination into the pages of his sketchbook. Working for high profile companies from IKEA to Renault. Talking to him, it’s easy to see how design became his calling. His profession is simply an extension of his passion, letting him expand his curiosity onto multifarious areas.

Published 13/02/2020

Photo by Omar Victor Diop

Half of Bibi’s time is spent in Senegal. Birsel + Seck, his design agency, has offices both in Dakar and New York. The cultural differences between the two fuels Bibi’s creativity. “We don’t need to defend design in the United States because design is part of the culture. Somebody in the States knows that everything around him has been designed but in Africa, in Senegal, it’s not the case. They don’t realize that even a pencil has been designed by somebody. A pencil, a graphic, a lighter, a chair, even a plastic chair made in China, has been designed. A $1 plastic chair or a $1 trashcan has been designed. They don’t have this mentality in their head.”

In Dakar everyone is a designer. Solutions are improvised rather than ‘designed’ in the haughty sense. Senegal may not yet value design culture but conversely there is an exciting speed to making things. Ad hoc reigns supreme, and it’s easy to find workshops. “Let’s say I will work on a project for Herman Miller. That project can take three or four years because you have meetings, you have Skype meetings, you have 3D file exchange. Too much politics. In Dakar, I can draw a chair and have it made in two days. It’s really energetic for a creative mind because everything is fast. Even a dress, a shirt, you do a sketch, you go to the tailor, and say, ‘I want a shirt like this or pants like this with a pocket here, blah blah blah”. Three days, the thing is there. Even for IKEA, I did my first prototype in Dakar.”

Bibi Seck Taboo stool, 2010. Photo by Martin Seck.

Bibi Seck Överallt rocking chair & footstool, 2019. Photo by IKEA.

There are three projects that Bibi currently has on the go in Dakar. “first, there is

my own product that I’m doing in Dakar. Using recycled plastic.” A material he has come to love for its thrift. New possibilities with recycled plastic are rife.

“Secondly, I started a collection called Simplicity and my goal is to make design affordable in Senegal. By applying a very simple design, the people who are going to make it won’t spend too much time and too much material. Simple shapes like a tube, metallic tube, you cut, weld, and you put on plywood and that’s it. A lot of people will say, ‘Design is too expensive’. I say, ‘Yes, design can be also very popular.’ ” This project is aimed at the local market and has to show people that design is a worthwhile venture.

“The third thing is I will do a couple of projects where I’m hired to do some interiors, I’m doing a co-working space.” It seems that co-working spaces are taking over the world.

«For me design is a profession whose main goal is to find solutions to problems and it’s not the problems that are missing in Africa, it’s the designers»

Published 13/02/2020

By DK Woon

Photo credits Omar Victor Diop, Martin Seck, IKEA

Mad Zoo

Wall Visions

The tiny apartment of Serigne Mansour Fall, aka Mad Zoo, is crammed with tightly stacked spray cans, hi-top sneakers and books. The walls are covered with art and photographs including a portrait of the artist’s young son, icons such as Angela Davis and Tupac, and Cheik Ibrahim Inyass. Mad Zoo’, “graffeur”, digital artist and painter, finds inspiration in sufism, history and hip hop.

Published 13/02/2020

CF

SMF

I founded it together with two artist friends, King Mow 504 and Krafts. We had the same vision, to change things around us and develop our art to the highest level. I was inspired by Big Key from a legendary crew in Senegal called Mizerables Graff, and hip hop culture, the style, the music and dancing. The RADIKL in our name means being rooted in our origins and traditional values of peace and tolerance, before opening up to outside influences. The K in Radikl, comes from the English word knowledge, while the L stands for “Leer”, the Wolof word for light, because we wanted to be a shining light, and a force against ignorance. Today, we are 16+ members, most of us from Dakar but some come from other parts of Senegal and West Africa.

CF

SMF

As a kid, I was always different from everybody else. Always in my own world, drawing, running in the streets. People in my neighborhood often called me crazy, in a bad way. When I discovered hip hop and graffiti, at the age of seven, I realized I was crazy in the right way, and had the courage to be and know myself. So, I embraced it. I’m the master of all crazy people! So that’s where the Mad originated. Zoo is short for my middle name, Mansour.

CF

SMF

Unemployment is high in the suburbs of Dakar, even if you have a degree. Stricter anti-immigration laws, that our own government support, have closed any legal way of going abroad to find work. Desperate people look for other solutions. Many travel across the desert, or take their chances on rickety boats, putting their lives at risk. All because they can’t find work and live with dignity in their own country. Some have died on the way. Others were sent back, having lost all their money and papers. They have to start again from scratch. Before they left they had little or no knowledge of the dangers that they would face. So we use the walls to inform them, give knowledge and support.

Mad Zoo traces the origins of Dakar street art to the Set/Setal protests (Wolof for “be clean/make clean”) in the late 1980s. Young people from Dakar’s poorest neighborhoods came together to clean up their streets and beautify their surroundings, picking trash and painting communal murals, sometimes referred to as the “talking walls” of Dakar. The legacy of graffiti as a positive, made by the people, for the people, lasts to this day. Graffiti has never been illegal in Senegal, something that is puzzling to writers in countries where the adrenalin rush of the chase is part of the thrill. In Senegal, the rush seems to come from giving back to your community.

«When I discovered hip hop and graffiti, at the age of seven, I realized I was crazy in the right way»

CF

SMF

Yeah, I’ll be part of anything that brings back humanity in the hearts of all people. I believe art can inspire mass actions that in turn can influence policy and, for example, change the situation of refugees and stateless people. We paint for a bigger purpose! We paint to serve!

CF

The Wild Style you use can be hard to decipher, is this a contradiction, since communication with the public is such an important part of your work?

SMF

I use wild style because it suits me aesthetically, but I also want to code my art, so that people have to go through a kind of inner quest to discover its essence. They shouldn’t just be able to come and find all the answers without effort. Meditation and internal questioning is so important for people, and I want them to find the answers themselves. My art is an art of interrogation, art of meditation, an art of awakening on spiritual reality which is the essence of humanity, our real richness.

Sketches from Mad Zoo’s blackbook

CF

SMF

Access is not an issue anymore, but we never saw the lack of materials as a barrier for our creativity or our work. The proof is that we still got respect around the world, even though we lacked good materials. In some ways it was an asset, because it helped develop real skills, working with only one cap and

making all the effects. Now, when we have more caps to work with, we feel very comfortable and can do whatever we want with sprays. It makes me really proud, after all those years of struggling to make Senegalese graff, African graff, known and respected. It means that we are moving forward. You know, our elders where drawing on walls with charcoal and sometimes used tar to fix their pieces. It was just in their dynamic to express themselves. I want to pay tribute to them for preparing the path, and also to the other generations for keeping it real until now.

CF

SMF

As an artist, spirituality helps me to fulfill my mission to serve humanity. What I love most about Dakar is its spirit of living together, in spite of any differences in culture, social background or religion. Sufism is a philosophy, a way of life that is at the core of all my work. I learn through meditation and prayers, and try to translate that into my actions based on truth, light and love. Not only love of God but love of humanity. I want to help people break through mental barriers, and discover their potential for making things happen. It’s about knowledge of self, self-love and self-determination.

CF

SMF

The wall tour is a way to bring graffiti and street art to all corners of Senegal where it’s not yet known or popular. We give local artists a springboard for showing their skills and exchanging experiences with others. It’s also the time of year when all our members unite and create a common piece, together with international guests from Europe, the US and other African countries. The most recent one was based around the spirit of Pan-Africanism.

CF

SMF

My personal dream project is to build a studio for producing graphic novels, comics and animated film. I’m setting it up together with other street artists. We also want to produce video games with characters inspired by African folklore, myths and legends.

Mad Zoo tribute piece to Elom 20ce, Kemit, Ibaaku & Bay Dam. Photo by Mad Zoo.

Published 13/02/2020

By Carmilla Floyd

Photo credits Petorovsky, Per Cromwell, Mad Zoo

Ibaaku

Loving the Alien

Published 12/02/2020

PHOTO BY ZIZI LAZER

RU

I

Dakar is a culture of different influences coming from everywhere. When I try to define it, in my heart, I might also be defining myself because it’s in myself. It’s a very colorful city. The people are so expressive and so beautiful, so stylish. It’s really inspiring on every level. From the spiritual to the physical, to the metaphysical. For me, and for my music, it’s the most important thing. To have that variety and diversity to challenge you all the time. You are in that continuous flow of so many things around you, and you try to focus. It’s the whole universe and, for me, the source of what I’m feeling. Dakar is the source of what I’m doing.

RU

I

I don’t know if it’s in the city’s DNA. Maybe it’s more a matter of that DNA being in this generation. A matter of how the world is working right now. The artists, the youths, are really sensitive to that, how the world is switching for the artist. How we have a lot of means to express ourselves. Maybe in the future we will really say that, ‘It’s in Dakar’s DNA’, but right now we’re switching it. We are working through all these possibilities we have as artists, as people, as human beings. But it’s more about the era we live in. It isn’t just happening in Dakar, it’s happening everywhere in the world.

RU

I

The first thing that comes to mind are the stories of people around me. It can be other artists, my family, friends you know, whatever, they all have stories. And I don’t enjoy just their words but their worlds, their individual worlds. At first you don’t know at all how it’s working but you listen and you look and suddenly you can see their individual world. That really inspires and motivates me.

PHOTO BY AKIBA HAIOZI

RU

I

First of all, I’m really proud to be associated with that movement with its great history, and to be recognized as a person pushing it forward. It’s a responsibility for me to bring my perspective from my continent about those subjects about our future, our mythology. What is our perspective for

the present?

What are we bringing to the table? What are the solutions that we imagine? How do we imagine the next year, the next century? For me, that means a lot of possibilities. It means bridges between the diaspora and the continent. It means a lot to me.

«There are actual aliens, you know. They’re around.»

RU

I

[laughs] “Both.

Certainly both. The album Alien Cartoon was the birth of the Ibaaku character, and aliens are very much a part of him. He’s a hybrid, his mom is an alien and his father is a human. The assemblage of that refer to a lot of things. My personal history, the idea of difference, the idea of the other. You can read the alien as immigrant or you can read the alien as an actual alien. There are actual aliens, you know. They’re around.

RU

I

RU

I

Actually, my next thing will be a collaborative project with the guys I’ve been on the road with these past few years. BenRichard, doing the visuals, and Alf, who’s a sound engineer but also an electronic musician. We are trying to concoct something. But, yes, at the same time I’m working on the next Ibaaku project. It will be an extension of what I did on Alien Cartoon but very different. I’m not saying it’s a new style but it’s a different aspect of what I did with the first one.

RU

I

Yes. That is how I want to evolve in art and music. Nothing inspires me more than other people, hearing the stories of other people and being around their stories. So, I will always collaborate because it always brings something new. There are no boundaries for whatever is coming in the future.

Published 12/02/2020

By Rikard Uddenburg

Photo credits Zizi Lazer, Akiba Haiozi

Zeinixx

The First

Graffiti in Senegal has a community feel. It’s not simply about making your mark felt. You rarely see tags. There is no current of rebellious backlash against the proverbial ‘man’. Instead it is a welcoming scene. I met with Zeinixx, the first female writer in Dakar, to get some perspective on graffiti in this energetic city.

Published 12/02/2020

DK

What is your name?

DS

DK

DS

DK

DS

When I was a teen, I saw myself as being Leonardo Da Vinci or Pablo Picasso. I was 14 or 15 years old when I started painting. I consider myself self-taught having never been to a fine art school. When I received my pocket money at the end of the month, I would buy equipment instead of buying jeans, shoes or make-up like other girls. I preferred to buy materials. It’s my passion, I love to paint. If I’m painting then I’m fine.

Graffiti I discovered watching TV. I saw guys in front of a wall with funny pumps. Then suddenly from nowhere came a painting. I said to myself, “Why not try this?” Having a larger canvas that’s big like a wall, that’s my thing! I asked a friend who told me, ‘Go see Graffixx. He’s at Africulturban.’ After school one day I went along to Africulturban and asked after Graffixx, and I said, ‘Hello I want to do graffiti.’ ” [laughs]

«When I was a teen, I saw myself as being Leonardo Da Vinci »

DK

DS

DK

DS

DK

DS

From the beginning, because when you start doing something you unconsciously develop your own style. It’s a school where you go through stages. Since I started I have been perfecting my own style, Maybe at some points I had a slower pace. Here, it is easy to doubt yourself, “Will I stop? I will stop… No I will continue.” Apart from that kind of moment, I’m always perfecting my work. Whether on a wall, shoes, a blackboard or in my blackbook. I’m constantly practicing.

DK

DS

My ambition is to see young women express themselves. Not to see women who want to do what I do, but can’t. Either for practical reasons or simply because that they are afraid. Because they are told that a woman’s place is at home in the kitchen. Or educating children, taking care of the family. It’s really beyond graffiti, it’s beyond hip hop. My ambition is to see women be able to perform in any field they want to move forward.

DK

DS

DK

DS

Published 12/02/2020

By DK Woon

Photo credits Petorovsky

Fatou Kande Senghor

Dakar’s Hip Hop Scene Queen

Fatou Kande Senghor is an artist, author, filmmaker and the founder of Waru Studio. We meet Fatou in a break from filming. She’s currently directing a TV-series that weaves together documentary and fiction on Dakar’s hip hop scene. A topic close to her as the genre that gave her a ‘lionheart’. Hip hop is her music.

Published 11/02/2020

The genesis of Fatou’s current series took a winding path. Initially it was all about giving back. “A couple of years ago I wanted to make a documentary about the music that has given us a chance to create our boldness. We come from families where, if you are a girl, you don’t talk back. Hip hop is challenging that. So this is the music I cherish and I owe something to.” At first, it seemed that all the pieces fell into place rather easily.

“I started filming all these people I knew. In Senegal actually most of the hip hop artists are my age or a bit older and I knew all of them. I started recording, taking photos, filming. Until I had too much material and it was twenty years down the line!” A film with such an amount would have been impossible.

“Because I couldn’t say anything valuable and use this material I decided to pour it into a book.” Wala Bok the book, came out in 2005. It is a remarkably comprehensive oral history of Senegalese hip hop.

What Fatou is currently filming though, shares the name of the book but will incorporate fictional elements that borrow from her own experiences. The series in works is being produced by Orange – the telecoms giant. Clearly Orange see something in the endeavour as there are to be 26 episodes.

As for when Fatou herself knew she was onto a winner – that moment of clarity came during casting.

“I started going to all these little contests. ‘This one has style. Oh this one has style.’ Then I found a girl. I found a guy. Then other girls and guys. That were perfect but the process was slow. So, one day I decided to organize a casting. To our surprise, when we opened the doors there were 2000 people out there.

The first ones, we could document ourselves. Thankfully they helped us document the others until everyone had their picture taken, holding up a blackboard with their name and phone number on it… Most of the people that showed up, had never been to a casting, they all thought they were part of the film already! So we’d get phone calls every day like ‘When am I shooting. Where should I go?’ That made us understand that the audiences would be there.”

«I organised a casting one day. When we opened the doors there were 2000 people out there.»

Fatou’s attitude to casting was informed by her respect for the skill and artistry of rap. She was casting MCs to act rather than the other way round. Actors are rarely convincing rappers but rappers can learn to act. “I wasn’t even surprised that the acting got so good. This is what they do. In hip hop you act. You’re in performance. Even when you’re not a real performer. You pretend a hairbrush is a mic in your room or in your mirror.”

With a cast of young performers, she set about making set life fun and vibrant. She’s been on sets before that were extremely tough. ”I didn’t want it to be too hard. I wanted to give room for actors to add in. I wanted to laugh while shooting. To have collective moments. And to document what hip hop has brought to all of us.” Her artistic interests in artwork, photography and streetwear all form a part of set life.

Espace Médina

Wala Bok is about more than simply hip hop. In it you will find themes Fatou would like to see discussed more in Senegal. Wala Bok’s central protagonist Mossane, faces challenges that will feel relatable to many Senegalese women. Her journey through the series will present hurdles that are commonly found. In Senegalese culture women are accorded what Fatou calls the “best virtues”. There are many family obligations that rest on Senegalese women. “If a mother falls sick, then it is the daughters responsibility to care for her rather than the son. If a brother has a child, it is the sisters that move into the house to give an extra hand. These obligations are strongly felt in Senegal.”

Obligations are not as ephemeral as they seem in Western society, they make things difficult for Senegalese female filmmakers. Sometimes funding might be difficult to attain when family obligations get in the way.

Fatou is not simply a filmmaker, though that would be quite enough on anyone’s plate. She has also carved out a role as mentor and trainer to a new generation of female filmmakers in Senegal. At 48, she’s older than them and is able to use her experience to navigate the system. The “Wind looks like it’s favourable now” for female filmmakers at the moment, but as Fatou knows winds change quickly. She’s on the watch out to ensure that gender issues don’t become tokenism.

Senegal has a strong cinema tradition, however this tradition has long been dominated by filmmakers shooting with foreign audiences in mind. Making films that were serious and arty. Previously Fatou’s films were documentaries and tended to be shown in the States. Often at universities.

For her upcoming series though Fatou has a different audience in mind. She is adamant her new series has to appeal to a domestic audience. For it to start conversations that put Senegalese society under the microscope. And maybe for it to even bridge generational divides. “Three generations of a family will be able to sit together and actually watch.”

Fostering a bond between old and young is especially important in Senegal with 60% of the population being under 25. Hip hop on TV might just be the perfect thing to gather a family round a TV set. It’s fun at the same time as serious. “The smallest kid knows about the latest artists. More mature kids go to school and know what is happening there. Parents want to know what kids are doing. Kids going through hard time and we explain why.”

«Hip hop on TV might just be the perfect thing to gather a family round a TV set.»

You are probably already getting a picture of Fatou as someone who concerns herself with the rights and wrongs of society. When asked what she would most like to remedy her response was forthright. “The educational system is my main target here. If hip hop can do so much for these children then it means somebody else has failed in the system.” Getting people to understand their own problems is a huge part of the battle. Learning is hindered by a system that bears the legacy of colonialism. Young Dakarois from the suburbs find themselves code switching when they come to town.

“If we’re even dealing with the language to start with. We’re being taught in French. If you take Dakar, there’s perhaps 3.5 million inhabitants. At the end of the day 1.78 million moves back to the poor suburbs. The ghetto. So they work here, attend school and *poom* you go back to the hood. You speak your own language. You act your own way. You eat your own food. You move in your own culture. You do all these things that are yours.” “Your house came before the sanitary systems and before the schools. So when you’re back in there it’s chaos. You can park anywhere, spit anywhere, piss anywhere and it’s fine. It’s what we do when we are here. When we’re not in the ‘civilised world’. But it means that your school looks like the ghetto. How can you learn anything when you’re speaking in a language that you barely use.”

Whatever comes of it, I feel certain that Fatou’s series will encourage the discussion that she’s so keen to see. I’m also sure it’s going to be an entertaining watch. A window into the world of Dakar hip hop that will hopefully broaden minds. “This music gave me a lionheart.” Hopefully many more lionhearts will be forged amongst the youth of Senegal.

Published 11/02/2020

By DK Woon

Photo credits Per Cromwell

Ken Aicha Sy

Giving the World to the Artists and the Artist to the World

Ken Aicha Sy is, in her own words, a mother, a manager, a producer and kind of a blogger. She runs a record company, several websites and her backyard is one of Dakar’s hottest creative hubs. She’s a woman on a mission, and her mission is two-fold: Making Senegalese people aware of Senegalese art, and then to take that same art and give it to the world.

Published 05/02/2020

RU

You went to design school in Paris before moving back here in 2010. Did they ever talk about Senegalese art ?

KAS

Ru

KAS

I do it for love. Artists have a lot of problems and a lot of them don’t have the money for, you know, communication and coaching. And I want us, as a country, to value our artists. When I got back here, I started to discover my country again. And all of a sudden, I realized how many artists there are that my generation don’t even know about. All the diversity, all the beautiful things they do – and nobody puts them in the light. I see the artist as an ambassador for the people. So the people should know them, because they’re working for the people. I decided to give the world to the artists and the artists to the world. Wakh’Art means speaking about art and that’s what I do. It’s a bridge between Senegalese artists and it’s a bridge between the Senegalese cultural scene and the world. But it’s not just a website or a network, it’s also an association for creating projects for young people.

«We have to have art in our society to have equilibrium, or people will go crazy.»

Ru

KAS

Yes. It’s called WAM. We felt there was no label in Dakar that shares our values. Today we have eight different artists on the label. Pop music, jazz, afrobeat, hip hop. Our goal is to give these artists a career that lasts. You know, not today or tomorrow, what do they want to do in maybe ten years? We do production, distribution, booking, all the work. And the artist gets to keep 70% of the money. I don’t see any other enterprise that does that.

Ru

KAS

I’m doing an exhibition in Berlin during the fall of 2019. It’s called Badaaye, future in Swahili, and it’s kind of a triptych connecting Afro-Futurism, fashion and design. It has a photography part and a video part where I interviewed three women and three men about Afro-Futurism and other questions about the future. I’m also trying to start a program for management in the cultural business. We don’t have a program for learning how to be a manager or a producer in cinema or music. I want to share my knowledge and we need teachers because we need to have people with vision and skills to really develop the industry.

Ru

KAS

Ru

KAS

Education. We have to give the people the keys to understand creation and creativity. So, education for the human being, education for the society and also education for the artist. education and stability. The artist is often alone here. We actually know that many Senegalese artists die alone of sickness, after all they’ve done for the country and people. That is not the way it should play out, not at all. That has to change.

Published 05/02/2020

By Rikard Uddenberg

Photo credits Petorovsky, Per Cromwell

Cheikha Bamba Loum

The Guardian of Espace Médina

Cheikha Bamba Loum is a wearer of many hats. He is perhaps best known as a fashion designer but nowadays functions more like a fine artist. Our introduction to Cheikha comes through Selly Raby Kane. To Kane he is somewhat of a mentor. They met in 2008 when he adjudicated a competition that she was entered in. Kane remembers their meeting fondly, “A very fun show. I think we connected because some of my elements made him laugh a lot but also he was wondering who is this person!”

Published 05/02/2020

Softly spoken, I find myself leaning in when he speaks to catch his words. He has a spiritual quality that inflects everything he says. Cheikha sees deeper meaning in everything. When asked what the purpose or message of his art is he replies, “To get people to really look at the world around them.” He has gone through a constant evolution. Never really being tied down to any one mode of creation. You can really tell that he comes from a family of artists and couturiers.

Cheikha’s fashion label was known as SIGIL. The brand focused on crafting elevated denim pieces, taking the utilitarian fabric and adapting it for the cities of Africa. When we meet Cheikha is dressed head to toe in denim of his own creation. The whole purpose of the brand was to create clothes capable of coping with a modern life. His constructions are light in weight and manage to cope with the heat without compromising on looks. Casual but in a put together manner. Anyone who hangs out with Selly Raby Kane is ever anything less than incredibly stylish and Cheikha is of course no exception.

In the past Kane and Cheikha were part of the Petite Pierre collective together. The name of the collective means small stones in French and their focus was to foster alternative voices in Dakar. The collective centered around a house in Dakar’s Oukham neighborhood that provided somewhere for like minded people to get weird. Houses are the center of social activity. Gatherings happen in the home, away from prying eyes. The notion of public space feels slightly different. You can enjoy yourself in a different manner when you know you are amongst friends.

And it is fostering another space that Cheikha is most focused on nowadays. He is custodian of Espace Médina. The space that he grew up in, where he spent his formative years, learning about life through seeing and hearing the artists that passed through. Médina is a cultural hub and Dakar’s equivalent to the Chelsea Hotel or Warhol’s Factory. And Médina can in fact trace its history back to the same era, finding its beginnings in the 60s.

Espace Médina

«Some things can be solved by religion. Others by art.»

To emphasize this point there is a combination of religion and art in Médina that might seem unusual to secular readers. The gallery space here is directly above a mosque. The two spaces are in conversation with each other. As Cheikha explains, “Each solve problems that the other cannot. Some things can be solved by religion. Others by art.” 92% of the Senegalese population is estimated to be Muslim and the majority of those belong to Sufi brotherhoods. Sufism is an inward looking form of Islam that underscores the believer’s personal relationship with God.

The desire to create dialogue through art, religion or simply intrigue is central to Cheikha as a person. If you’re ever in Dakar, a visit to Médina is bound to spark some interesting [if not even skewed] conversations.

Published 05/02/2020

By DK Woon

Photo credits Per Cromwell

Papi

L’Artpreneur

If you’re in Dakar looking for art, clothes, music or parties you will almost certainly bump into Mamadou Wane aka Papi. Chances are that even before you came, you checked the city out on the Instagram feed Dakar Lives and, wouldn't you know it, he and his friends created that too! There sure are a lot of jars in Dakar and Papi has at least one finger in each one of them.

Published 04/02/2020

RU

Tell us about Mwami, your clothing line.

P

Mwami started about four years ago. It was just a logical thing for me, like a need. What am I looking for? Am I finding it? If not, I believe I have a voice, because I see design as language. So Mwami is me answering a question, it’s me saying I don’t want to just be a consumer in life. Anything that I wear, anything that I use has to be beyond just an object. What’s the story behind it, what does it mean? Where is my dollar going? I was not seeing the right fit on the market for myself as a consumer, so I started making things for myself.

RU

P

Yeah, it’s a blessing and a curse. I have this issue that I’ve been dealing with for a couple of years that I’m not creating enough art, because I kind of entrapped myself in this ‘artrepreneurship’. You start with the artwork and you decide that you’re going to extend it and ‘art-erprise’ so you can use your creativity to generate the revenue which allows you in turn to keep the art pure. But it’s so easy to get eaten alive by your own business and you end up with not enough time to paint. I try to create moments for myself where all I need to do and all I have to do is make art. I turn off the phone and go away.

«I believe I have a voice, because I see design as language.»

RU

You take a time-out for art ?

P

Yeah. I go to new places, I have conversations with new people, I eat new food, I take time alone. And, you know, any artist that wishes they were more productive because of whatever they’re dealing with can tell you that the inspiration is not the issue. On the contrary, you have all these ideas that need to come out. It’s only really a matter of sitting down and getting to it.

RU

P

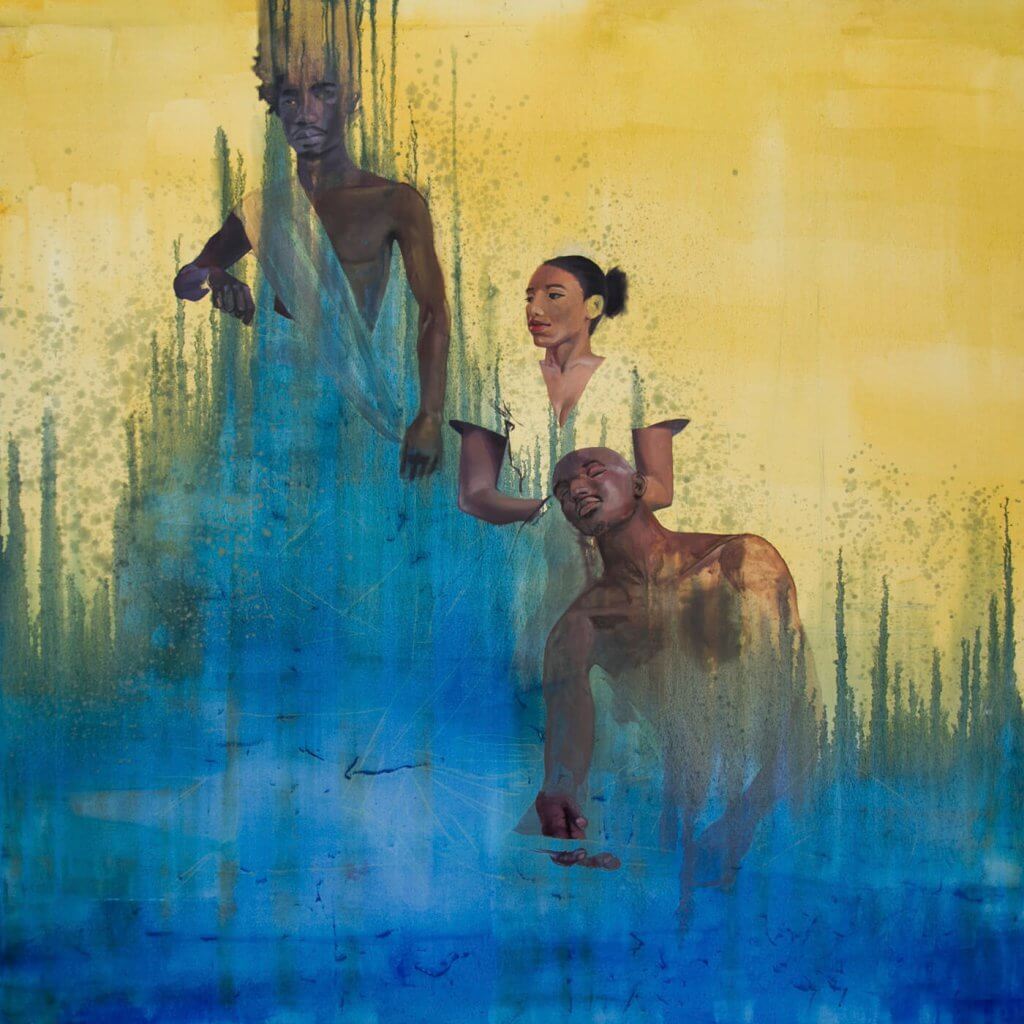

Well, I have a few things that I’m interested in, and I have images in my head. Sometimes full paintings done in my head. What I’ll do is I sketch, I sketch a whole lot, and I use a lot of photography to kind of just build this trove of images that live in my mind for a while. I do a few sessions of live drawing or live painting. Then I start to paint with a very clear image in my head, which develops as I’m painting and turn into something different or something more minimal or more archaic than what I had in mind. So, it’s an evolutive process. It’s not a step-by-step, for sure.

Papi Bermudas II, 2016

Papi Bermudas III, 2016

RU

P

Am I a struggling artist? [laughs] No.

I think I have this duality of the airy, floaty vibe to me and then there is the very down to earth thing. I think it comes from my background and my upbringing. I sure have moments where it’s total chaos at the studio or I’m on an island, and I find a little bit of paints and I’ll go meet with the local painters. We try to put together a frame and then I’m going crazy with it, just throwing shit all over the place. Then I try to refine it, or I just leave it raw.

Then there will be other moments where I’m doing a residency at a hotel somewhere and there isn’t a speck of paint on the wall or on the floor. Things are very clean. I’m using gloves. I have this beautiful apron that’s embroidered from my clothing line, and a camera is capturing the process. I don’t know, it’s moments. I really just am speaking through pixels or paints or colored mud, and when you’re speaking, sometimes you’re yelling. Sometimes you are speaking very calmly. Sometimes you have this entire speech, an entire monologue prepared in your mind. Most times you’re just free-styling, and that is, I think, why my work looks the way it sometimes do.

RU

P

I think I see that as the same thing, really. It’s the same way for the clothing line. Sometimes I may use traditional hand-done embroidery, and then other times I want to think of seven different ways of having one logo or one pattern done. And I need it done now, and I need an entropy of different combinations of colors and lines. So I’m going to use digital embroidery to make that happen, obviously. I’m going to use a software, and I’m going to layer different patterns until I’m happy with it. I just can’t accept that I have to limit myself in my creativity because I’m confined to one media. That’s not happening. I have one language and multiple words. If that word is oil paint or if it’s spray paint or if it’s a crazy brush or Photoshop, I’m going to use it.

Papi Bermudas I, 2016

RU

P

Absolutely. Especially now that I’m doing all these other things and sometimes It’s just so much and, you know, it’s good to have the one thing that I can always revert to. That I know whenever there’s confusion, whenever it’s cloudy, I know exactly where to go to find clarity. When there’s a lot going on and your processor is jammed, right? You’re all out of RAM, 4 gigahertz isn’t enough and it’s almost like an automatic reflex; Oh, I’ll go paint. I’ll make a sculpture. I’ll take some photographs.

«Whenever there’s confusion, whenever it’s cloudy, I know exactly where to find clarity.»

NS

P

I lived here one year when I was a kid, but I was born in Mali. I grew up there until I was a teenager and then spent the rest of my teenage years in East Africa. Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda and after that I went to military school, then art school, in New York and Connecticut. I went for a holiday in Dakar over the summer and I just stayed. I was supposed to be here for a week but, you know, here I am. I’ve been here almost six years now, came here in 2013. I didn’t leave for three years and I haven’t left the continent since.

RU

P

It wasn’t even really a choice for me to live in Africa. It’s just my reality. I grew up knowing that I would live here. It’s just a matter of picking the city. Dakar is just the city that made most sense to me in terms of lifestyle and opportunities and where I saw myself fitting in as an artist and as a young person building something. Dakar is the one for sure. It’s the place.

RU

P

It just is, man. It’s a fact that it’s cool to be an artist in Dakar. We already know about Lagos, we know about Jo’burg, we know about Nairobi and technology and innovation and Addis Ababa and Kigali. But Dakar is this place where it’s very clear that people can see the buzz, they can feel the vibe, they can sense the energy. This is the one, man, this is the one. It might not be the biggest market. You might want to go sell your clothes in Lagos or Abidjan, you might want to go to a festival in South Africa. But you want to create here, you want to exchange with others here. You want to go to a party on the beach or by the monuments. This is where you want to be. Really. This is where it’s happening.

Published 04/02/2020

By Rikard Uddenberg

Photo credits Petrovsky, Per Cromwell, Papi